Stop “Investing” in Ad Channels: They're Consumables, not Investments

Why Your Mental Model of Media Buying May Be Wrong--and How to Fix It

The Myth of Investing in Ad Channels

Wall Street’s1 "buy low, sell high" mentality has permeated nearly every aspect of modern business.

“Get in on the ground floor”

“Early stage opportunities2”

“Exponential growth potential”

Startups thrive on this approach, turning early equity investments into massive returns3.

When marketers are on autopilot, they’ll apply the same mindset to advertising—but they’ll find themselves chasing ghosts.

Media buying is not the same as investing in a startup, and treating it as such—even using the term ‘investing4’—is a misapplication of a mental model.

…Swiss fashion house Philipp Plein hit headlines recently with the news they had bought a plot of land in [the metaverse] worth a massive $1.4 million….

[This investment is] evidence that some brands don’t see the metaverse as some passing craze, but as something that is here to stay and worth investing in.

—Basis Technologies, “Advertising Opportunities in the Metaverse“

This mistake leads to wasted budgets and a skewed incentive structure.

In this article, we’ll explore why the ‘investment’ model doesn’t translate to ad channels, how experimentation should be approached, and the importance of focusing on fundamentals in media buying.

The Startup Equity Mentality: Why It Works for Startups

Startups are a game of exponential5 growth potential.

Early investors put money into an unproven idea. They’re betting that its value will increase over time.

This is why you buy ‘shares’ of a company—you’re literally buying part of the shared pool of company ownership

It’s like buying a plot of land and hoping you can drill oil from it. If you’re able to, someone would be willing to pay you more than you bought it for.

It’s a 'get-it-and-forget-it’ purchase.

If the startup succeeds, the investors own the same percent slice of a now-much-bigger pie. Early shares retain their value relative to the size of the business.

When they’re ready to close the position, investors make their money by selling their shares to someone who values them more6.

This model works because your initial investment remains intact.

It appreciates over time as the startup grows, gaining value without further input from you.

This is why venture capital firms tolerate high risks: the payoff from one massive success can outweigh the losses from several failed investments.

Ad Channels are Vending Machines, not Investments

The same principle does not apply to advertising.

When you ‘invest’ in a new ad channel, your "investment" is consumed immediately—it funds impressions, clicks, or views.

There’s no equity to retain and no future buyer waiting to offer a premium for your “share” of the channel.

The only way to profit is by generating sales or leads for the rest of your business to capitalize on. If the channel underperforms, you’re left with nothing to show for it—except lighter pockets.

You’re buying a candy bar from a digital vending machine—the value of the consumption has to be worth the purchase price.

Even in the best-case scenario where a channel overperforms, you must continuously re-buy new ad placements to maintain those results.

Unlike startup equity, ad spend doesn’t appreciate—the intrinsic value depreciates (to 0) as soon as it’s used; the resulting customer behavior has to be worth the spend.

This fundamental difference is why media buying must be continuously monitored and managed, especially when venturing into new, unproven channels.

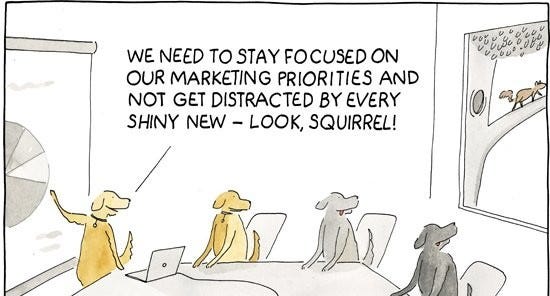

The Sexy Channel Syndrome 👙

There’s another important factor at play: the allure of trendy, new platforms.

Marketers are eager to be seen as pioneers.

They’re ready to share success stories about how they “cracked” a cutting-edge channel.

They’re excited to be first somewhere like the metaverse or Threads.

This tendency isn’t necessarily driven by performance—it’s about reputation.

Sharing a success story from a trendy channel at a conference or cocktail hour (or on LinkedIn) conveys gravitas.

Reporting consistent, solid results from a boring but reliable platform like TV does none of the same.

This creates a skewed incentive landscape.

Instead of allocating budgets based purely on ROI, marketers are tempted to chase channels that bolster their personal reputation.

The result?

Misallocated budgets, poor returns, and inflated expectations for channels that may not have staying power.

R&D or Recklessness?: The Role of Experimentation

Read my lips: experimenting with new channels is worthwhile.

Advertising is an evolving landscape, and brands that fail to adapt risk falling behind.

But experimentation should be disciplined and purposeful—not reckless trend-chasing.

New is not always better—often, new is worse.

A portion of every budget should be allocated to R&D. The key is setting clear hypotheses and success metrics before diving into a new channel.

What’s the expected ROAS?

What’s the timeline for determining success or failure?

What are you using to measure this?

By treating experimentation as a structured process, you can mitigate risks while still exploring growth opportunities.

Don't Let Your Marketing Failures Stay Failures

Check out this post about how to pre-plan your marketing experiments so that you're meaningfully learning with whatever a result is!

However, knowing when to cut your losses is equally important.

If a channel fails to meet expectations after reasonable testing, don’t fall into the trap of doubling down to “make it work.”

Good experimentation requires the discipline to walk away when something doesn’t pan out.

Allocate 10-20% of your budget for experimental channels.

Do not go over this to ‘prove’ something on the edge of statistical significance—practical significance matters more, and you’re probably not there if you’re chasing near-threshold values.

Use specific, pre-defined KPIs like ROAS > 2x or CAC within 15% of established channels to define “success.”

How to Extract Value from Transitory Advantages

Occasionally, early adopters of a new ad channel can benefit from temporary inefficiencies.

For example, TikTok’s early advertising days offered incredibly low CPMs as the platform worked to attract brands. Marketers who recognized this opportunity and moved quickly saw outsized returns before other companies started buying in and the cost per ad reached a steady state.

These transitory advantages can be valuable, but they’re fleeting.

The market inevitably catches up, driving costs higher and reducing ROI (sometimes to entirely irrational levels). The danger lies in assuming these advantages will last forever.

Too many marketers continue pouring outsized budgets into a channel long after it has lost its edge—at the expense of more effective alternatives.

Treat these opportunities as what they are: windows of opportunity.

Extract value while you can, but always reevaluate whether the channel still makes sense for your strategy.

Back to Fundamentals: Sustainable Media Buying

It’s easy to fall into Shiny New Object Syndrome, but sustainable media buying requires discipline.

At its core, advertising is about delivering measurable, meaningful results.

That means focusing on fundamentals.

Check out the article below for a deeper dive:

By grounding your strategy in these fundamentals, you can navigate the shifting currents in the world of media buying without falling victim to fads.

Know what you’re buying; know what lasts; know what is consumed.

Caveat emptor.

Silicon Valley's too now

I’m not suggesting that you can’t get outsized returns by being an early mover on a new ad channel, but I am suggesting that the market is pretty efficient and will adjust bids to meet the proven results.

Sometimes

No, I’m not suggesting that a persistent, long-term reapplication of marketing fundamentals in the same place is a mistake. I am suggesting that a different term than ‘investing’ should be used to allay any confusion

Important to note that exponents go both ways!

This is the "greater fool" principle, where someone else is willing to pay more for the same asset.

This is all spot on, the only thing I'd pick a bone with is that I think the "transitory" benefit can persist for a long time. When I was coming up in paid search, it probably took 10 or 15 years before rising prices and budgets took all the underpricing out of the market.