Excellence Isn’t One-Size-Fits-All: Why Your Philosophy is Slowing You Down

How marketing can work *with* other teams instead of against them

In the early 20th century, IBM mandated crisp white shirts and dark suits to mirror the formal attire of its corporate clients, showing they wanted to work with their clients.

But as client workplaces grew casual by the 1980s, IBM’s rigid dress code persisted, clashing with the times.

Originally meant to align with customers, the “blue shirt” became a symbol of adhering to dogma—until 1995, when IBM embraced more casual attire, rediscovering the true intent: adapt to the client, not the rule.

The output of ‘excellence’ in customer service changed with the times

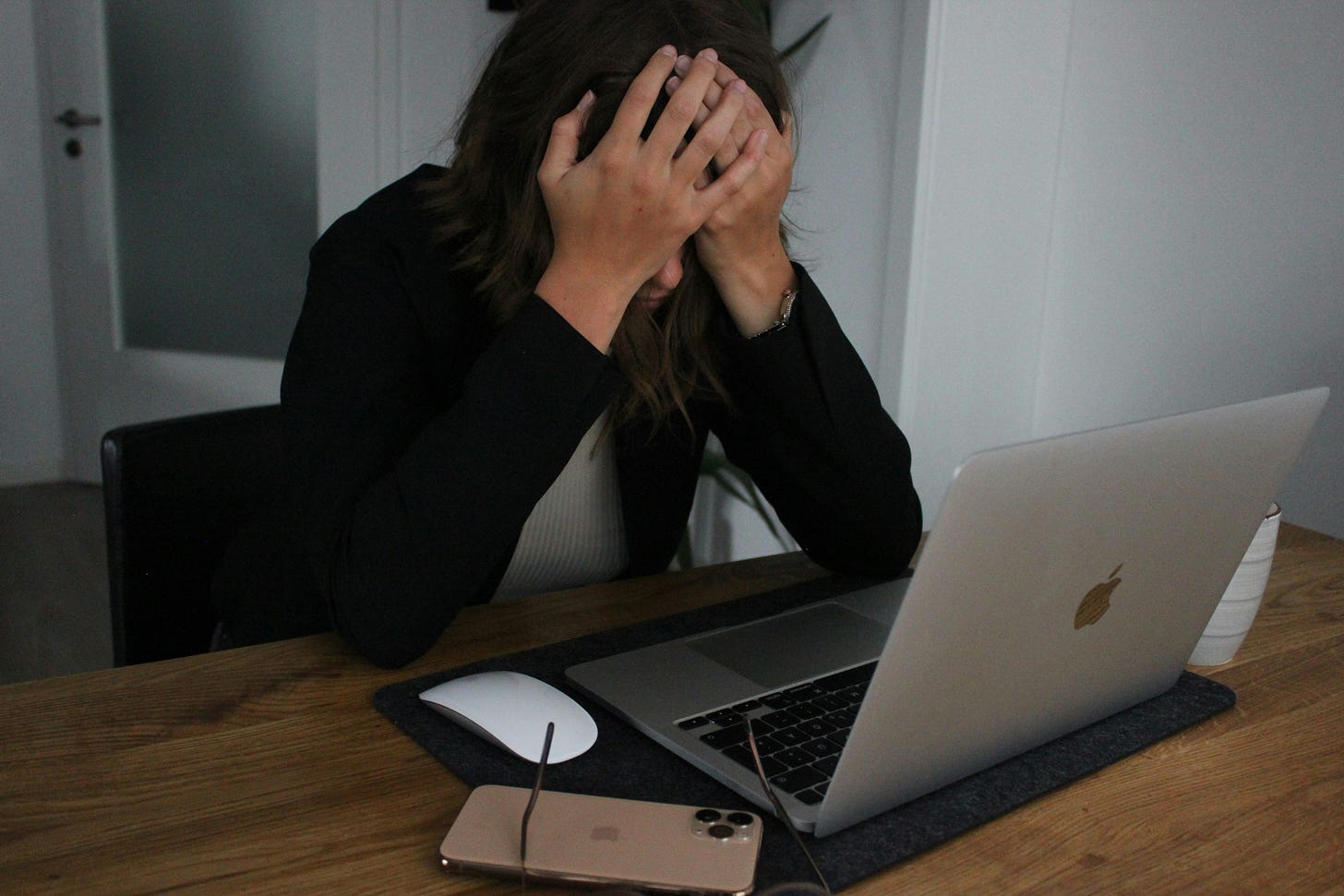

A marketing manager and an engineer are locked in a heated debate.

The marketer is pushing for a quick product launch to capitalize on a trending market opportunity, while the engineer insists on conducting more rigorous testing.

Both are hard, good workers.

Both strive for "excellence."

Both have definitions that couldn’t be more different.

This scenario plays out in businesses worldwide, slowing down progress and building resentment.

Misalignment on what constitutes "excellence" can be a significant roadblock, especially when it comes to developing digital products.

Different business domains—whether it’s aviation, tech startups, or marketing—have their own unique perspectives on what makes something "excellent." These differing views can create friction, leading to delays, rework, and frustration.

But why does this matter?

Businesses can’t afford to be bogged down by internal disagreements over quality—there are plenty of headwinds from outside your business. Understanding and reconciling these diverse perspectives is crucial for moving forward efficiently.

Just as data needs context to become valuable, so too does the concept of excellence require a shared understanding to drive business success

.

What Is Excellence? The Greek Concept of Arete

To grasp why different perspectives on excellence can be an issue, we first need to understand what excellence really means.1

The ancient Greeks had a term for it: arete.

In book 1 of Plato’s Republic, Socrates debates (mainly) Thrasymachus (a sophist) about the nature of justice.

Arete refers to excellence or virtue that’s specific to its context.

For example, the excellence of a knife lies in its sharpness, while the excellence of a rolling pin lies in its ability to roll dough.

You wouldn’t want a sharp rolling pin or a dull knife—each tool has its own measure of quality based on its purpose.

This sounds obvious. But it’s easy to get stuck in whatever their main domain you regard ‘excellence’ as and struggle to adapt.

In the business world, this concept translates directly. Each domain has its own version of arete:

Aviation: Excellence means reliability and safety. A plane that doesn’t fly safely isn’t excellent, no matter how quickly it was built.

Tech Startups: Here, development velocity and the ability to iterate quickly are prized. Getting a product to market ASAP, even if it’s not perfect, is be more valuable than waiting for flawless execution.

Marketing: Speed to market and positive consumer sentiment are key. A campaign that resonates with customers quickly can outperform a meticulously planned but delayed initiative.

These differing definitions are like trying to agree on the best pizza—it depends on who’s you ask!

When teams from these diverse backgrounds collaborate, their differing views on ‘excellence’ can clash, leading to misunderstandings and slowed progress.

Why Misaligned Perspectives Cause Friction

When cross-functional teams come together, they often bring their domain-specific notions of excellence.

For instance:

A marketer might push for developing a more customer-pleasing product experience (think of how nice it is to open a new iPhone box). Or try to play up the ‘purity’ of a supplement.

A manufacturing manager accustomed to being judged on large-scale spec-alignment might resist changes that the marketer tries to make on a process that seem ‘useless’ because they don’t affect getting a product into spec.

These clashes aren’t just minor disagreements; they can lead to delays, rework, and a general sense of frustration as teams talk past each other. Each side believes they’re advocating for the best outcome, but without a shared understanding of what "quality" means, progress stalls.

This misalignment is similar to the challenge of interpreting data without context, as outlined in the DIKW model for turning data into knowledge.

Just as raw data needs context to become meaningful information, project specifications need a shared definition of excellence to guide effective collaboration.

Case Study: Legacy Enterprises and Digital Products

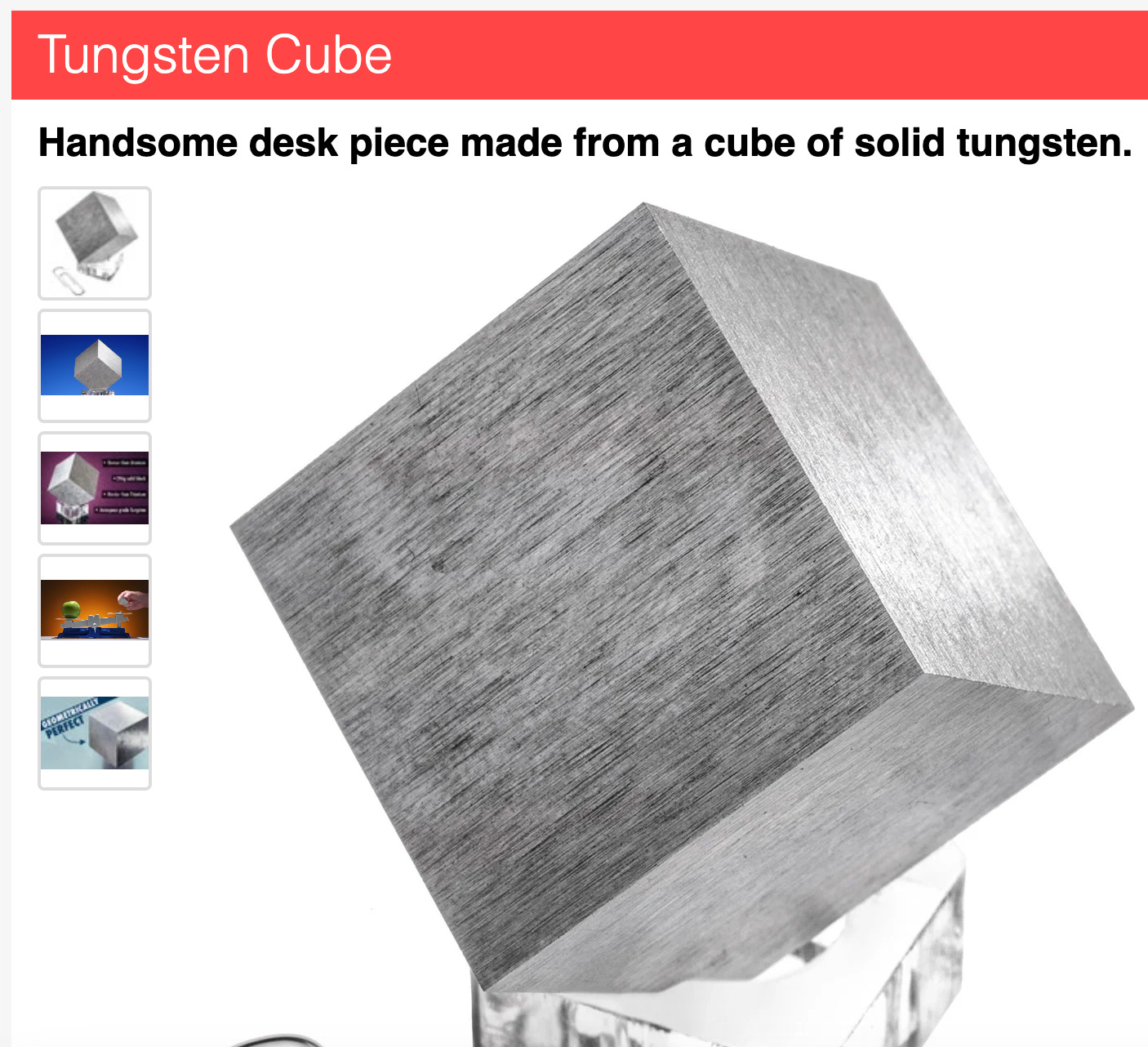

Consider a legacy enterprise like an aluminum refinery.

In this environment, excellence is traditionally defined by alignment to specifications, consistency, and safety.

Every machine, process, and output works together to produce the output to exact specifications.

More pure aluminum is not ‘higher quality’ because its sold as a commodity. Aluminum in cleaner ingots is not ‘higher quality’ because asthetics don’t affect price.

This focus has made the company successful in its domain.

Imagine this same company attempting to add a product line.

They want to develop in-house marketing processes to sell ingots to individuals. [For some reason, pure metal cubes have become a trending desk toy]

The culture that excels in manufacturing—building to exact specs and maintaining strict processes—doesn’t translate well to another field.

Marketing to individuals requires focusing on things that don’t matter to commodity refineries:

the unboxing and ordering experience

how clean the product is (no residual refinery oil from the processing)

how easy the product is to order (no phone-only order forms)

And the manufacturing team is driven crazy by the things marketers downplay:

The exact price of the product (commodity products are made with tiny margins—consumer products are more fluid)

The purity specs (consumers who want a desk toy probably don’t care)

As a result, a successful, hardworking employee that’s found success in manufacturing risks falling behind competitors who can adapt more quickly to the different landscape of consumer marketing.

This struggle highlights the importance of aligning perspectives on excellence, especially when venturing into new territories like digital products.

Why Digital Products Are Different—Information

So, why do digital products require a different approach? The key lies in how they derive value.

Note: In this context, I refer to digital products where the main value is the user’s actions after being informed by the tools.

A ‘digital product’ of robotic firmware that requires no human interaction should be designed to exact, preexisting specs—if a robot breaks, thats a physical product problem to resolve. You can’t just ‘reset’ a broken servo.

‘Information Products’ might be a more accurate term.

Unlike physical products, which prioritize consistency and perfection (e.g., every aluminum batch meeting exact specs), digital products derive value from actionable insights and adaptability.

Consider a predictive feature in a driving app: knowing and alerting you that there’s a 30% chance a car will merge into your lane a minute in advance is more valuable than being 99% certain just a second before it happens.

The former gives you time to react, while the latter is too late to be useful. This illustrates that in digital products, timely insights often outweigh perfection.

This difference is crucial because it demands a shift in mindset. Digital excellence isn’t about achieving flawless execution from the start; it’s about delivering value quickly and refining based on real-world feedback. This iterative process is foreign to many legacy enterprises, making the transition challenging.

Moreover, as discussed in our previous article on the DIKW model, digital products excel at turning data into wisdom rapidly. They require a mindset that embraces change and prioritizes user needs over rigid specifications.

How to Bridge the Gap

Acknowledging that different perspectives on excellence are inevitable is the first step.

Once you have the painful “What language are we speaking on this project” conversation, the rest becomes smooth sailing

The challenge is manageable with the right strategies:

Shared Language: Develop a common definition of excellence for cross-functional projects. For example, agree that "excellence" means "delivering value to users quickly and reliably." This shared goal can align teams despite their differing backgrounds.

Cross-Training: Expose teams to other domains. Let marketers shadow engineers to understand technical constraints, and vice versa. This builds empathy and a broader understanding of what excellence means in different contexts.

Culture of Understanding: Encourage legacy teams to experiment with agile methods in low-stakes projects. Push agile development teams to walk the floor of a factory to understand that ‘move fast and break things’ is the wrong approach for physical products

Conclusion

Differing perspectives on excellence can significantly slow down businesses.

These misalignments create friction, leading to delays and missed opportunities.

By fostering a shared understanding of quality and embracing the unique demands of digital products, companies can overcome these challenges.

Leaders must take the initiative to create a common language for excellence and encourage cross-functional collaboration.

Remember, excellence isn’t universal—it’s context-specific, as the concept of arete teaches us. But by understanding and respecting each other’s contexts, teams can work together more effectively to drive innovation and growth.

So, the next time you find yourself in a debate over what makes a project "excellent," take a step back and consider the perspectives at play.

Sorry for having to go back to definitions, but this is a slippery topic! Its needed