How Much is AI Glenn Powell Worth?

Philosophers tell us 'what', economists tell us 'how'

Note: I did nearly zero research on Glen’s finances But one article gave me numbers from “Anyone But You”, so we’re gonna roll with that.

How much is an AI Glenn Powell worth?

To a studio, an AI Glen Powell is probably worth 750MM.

How do we get that?

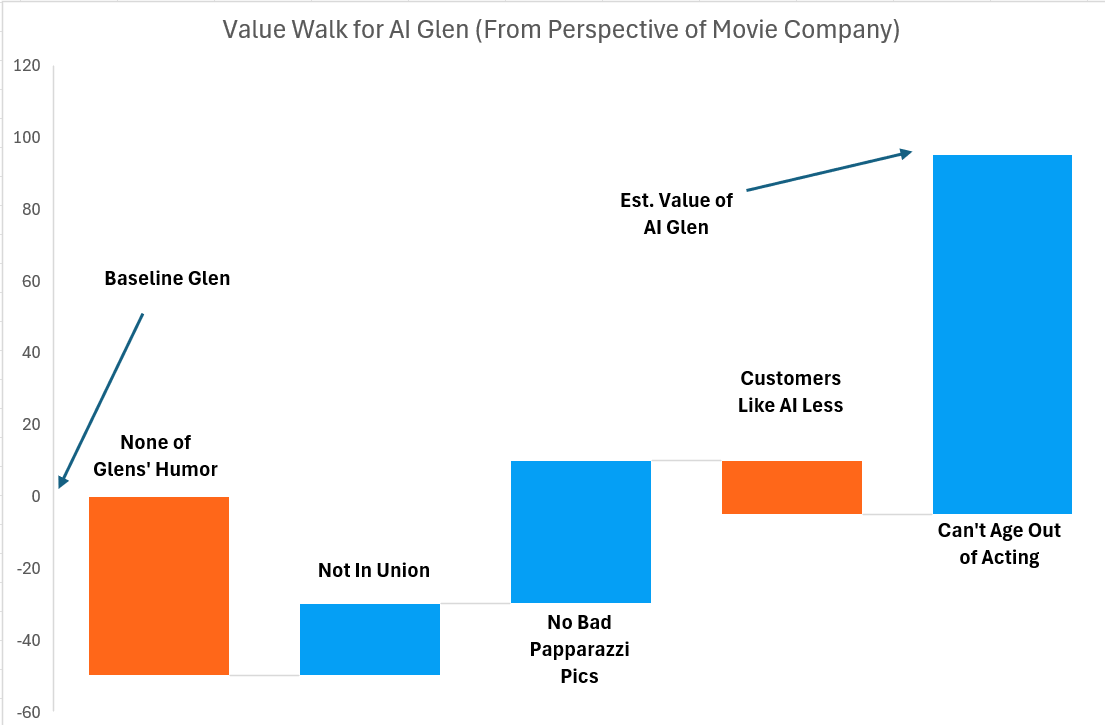

You could start by doing a value walk of how much it’s worth vs the existing Glenn.

We end up with a 100% increase on natural Glen value. And we didn’t incur the normal Glen cost.

He earned 5MM for Anyone But You, implying he made the studios at least that much. Most professional services are 2x markup on variable cost (10M)1.

If AI Glen could work 3x movies as human Glen (30MM/year), and could work as long as no one noticed that ‘he’ wasn’t aging, he could get 25 more years (750MM).

750 Million!

The negatives (e.g. customers don’t like AI Glen) are big.

But when have qualitative customer preferences beaten a cheap alternative?2

Consistency is Key.

The most enjoyable parts of AI Glen aren’t going to ever beat natural Glen—but that’s not why AI is worth more.

A hardwood floor is always more appealing than a laminate floor, excepting cost, which is the most important thing.

Year-over-year consistency, a lower cost, and longer depreciation period is worth a 0% risk of paparazzi meltdowns (to a studio).

Consistency Beats Quality

If AI Glen is worth so much, why aren’t all movie stars digital?

Selling out is usually more a matter of buying in. Sell out, and you're really buying into someone else's system of values, rules and rewards.

The so-called "opportunity" I faced would have meant giving up my individual voice for that of a money-grubbing corporation.

It would have meant my purpose in writing was to sell things, not say things. My pride in craft would be sacrificed to the efficiency of mass production and the work of assistants. Authorship would become committee decision. Creativity would become work for pay.

Art would turn into commerce.

In short, money was supposed to supply all the meaning I'd need.

—Bill Watterson, Kenyon Commencement Speech 1990

You’re exactly right to ask that!

The real question is ‘how long can human movie stars stay on top?’

Once we have a number in a spreadsheet, financial firms will jump in on the action and develop our new tech.

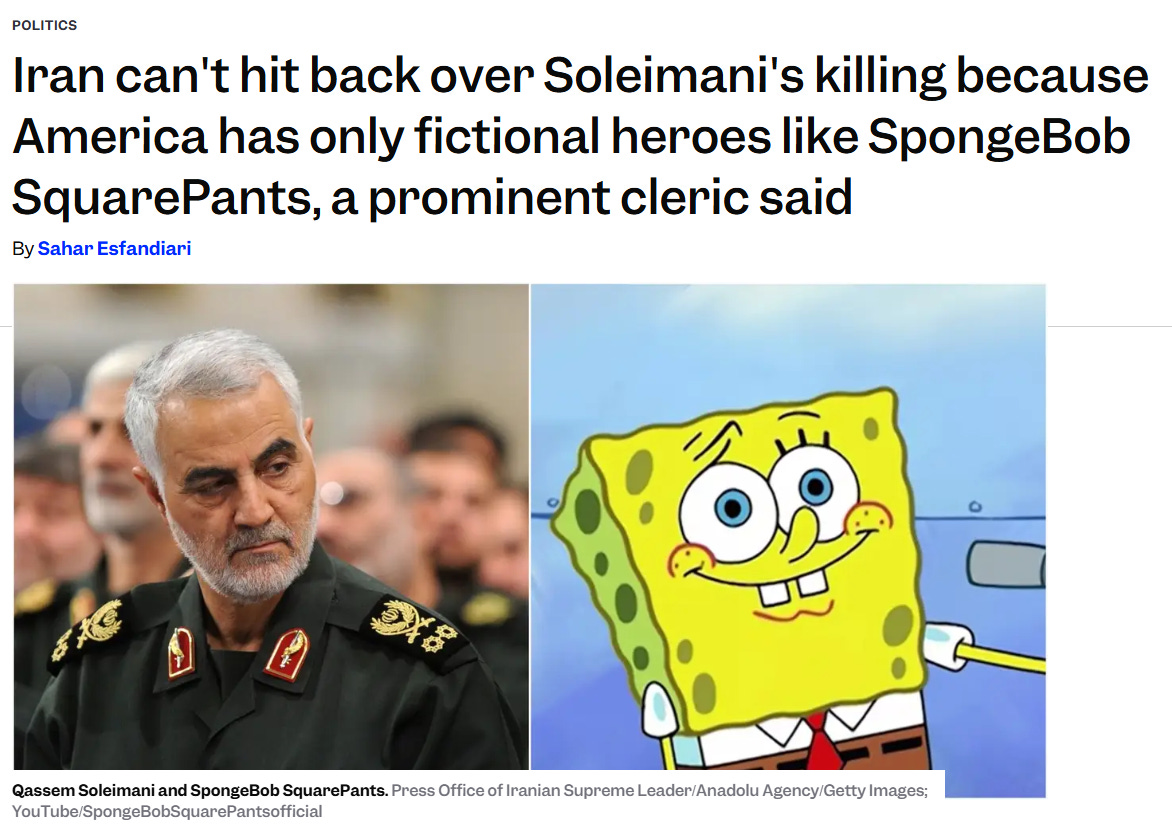

If we’re hurling towards a future of all AI movie stars—why even bother to simulate a real human?

Why wouldn’t we aim for the perfect processed commodity? Something entirely unoffensive.

We will.

Media philosophers told us where we’re going, but economists explain how we get there.

Economists are sometimes right, unfortunately.

Their entire field—which I often lampoon—provides business practices’ mechanism of action. They can’t tell you where broad societal trends will take humanity.

But they can tell you where businesses will likely allocate capital if unconstrained by other guiderails.3

They agree that a business with very regular revenue is worth a lot.

Consistency is more important than almost anything else4.

Economists have built a world where we can quantify how much consistency is worth—and thus explain the inevitable ‘slippery slope’ of AI actors.

Q: What does this have to do with marketing & media?

A: Business valuation practices (econ) have important downstream media and cultural implications on marketing

Culture’s Downstream of Econ?

Yes—the economics of things affect culture.

And big studios know that. If they could sell 500,000 concert tickets at half price, they would do so in a heartbeat.

They know that having 500,000 people talk about ‘last nights concert’ is a great way to have free marketing.

But 500,000 people can’t hear a musician at a concert.

Right?

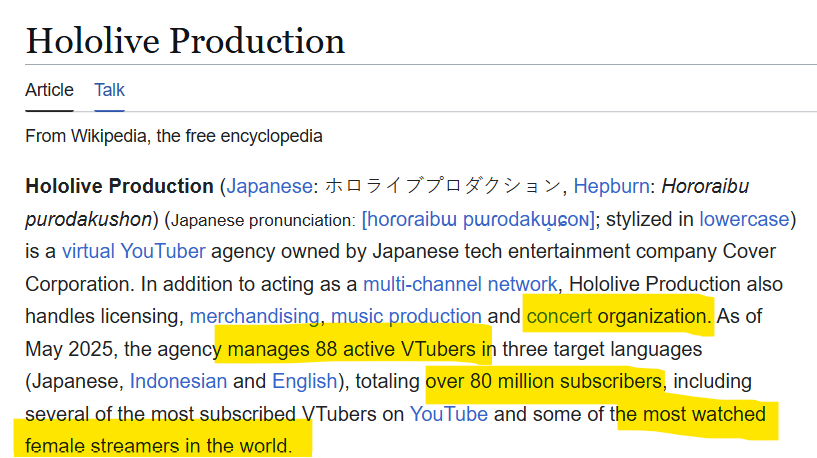

What if you could render what your audience perceives and the source without any of the messy human parts?

We’re already going there.

Welcome to the future

Conclusion

The economic incentives driving the potential adoption of AI actors like "AI Glen Powell" reflect the final proof that media theroists were right.

The future wasn’t always Progress; its the one that philosophers like Jean Baudrillard, Marshall McLuhan, and Guy Debord warned us of.

Baudrillard's hyperreality, where simulations become more "real" than reality itself, is eerily manifested in the growing market for consistent, controllable AI actors over their human counterparts.

McLuhan's ideas of the ‘global village’ shows that performance and stardom5 is redefined by the massive reach and new audience of technology.

Debord's "society of the spectacle" becomes even more relevant today. We’re approaching a future where our cultural icons are literally manufactured spectacles6, optimized for economic efficiency rather than authentic human expression.

The economic logic presented in this article – valuing consistency, cost-effectiveness, and longevity over the unpredictable brilliance of human performers – demonstrates how market forces can accelerate our journey into this philosophical quagmire.

As we stand at this crossroads where technology can usurp wholly human roles, we must find non-economic guardrails to guide commerce and culture.

Currently, the pursuit of economic optimization is at odds with our cultural values.

Are we willing to quietly commercialize and the essence of human creativity that has traditionally defined performing arts?

Unless things change, probably.

These are gross oversimplifications.

Transistor Radios: Initially met with skepticism over sound quality; became dominant due to portability and affordability. Now the only version available

Gypsum Drywall: Replaced traditional plaster despite initial concerns; gained acceptance for lower cost and ease of installation. Now standard

High Fructose Corn Syrup (HFCS): Faced backlash as a sugar alternative; became ubiquitous due to lower cost and versatility despite customers’ preference for sugar flavor.

Plastic Bottles: Preferred glass bottles for feel and strength; plastic became standard due to cost, weight, and convenience.

For example, a perceptive political figure might discuss how consumerism came to replace the role of social and religious community.

[In] Lasch's most famous work, The Culture of Narcissism: American Life in an Age of Diminishing Expectations (1979)… Lasch posited that social developments in the 20th century (e.g., World War II and the rise of consumer culture in the years following) gave rise to a narcissistic personality structure, in which individuals' fragile self-concepts had led, among other things, to a fear of commitment and lasting relationships (including religion), a dread of aging (i.e., the 1960s and 1970s "youth culture") and a boundless admiration for fame and celebrity (nurtured initially by the motion picture industry and furthered principally by television).

—Wikipedia summary of Christopher Lasch

But just listing the results is like saying that ‘people who take cocaine talk quickly’—it’s an accurate, but not mechanistic, description of a phenomenon.

Economists provide an explanation of the incentive space (and its primary associated metric—money) for how we get there. See footnote 4 for more examples of relevant metrics that affect behavior without being money.

In the cocaine example, a scientist might say:

Cocaine binds and blocks monoamine (dopamine, norepinephrine, epinephrine, and serotonin) and reuptake transporters with equal affinity.

Monoamines accumulate in the synaptic cleft resulting in enhanced and prolonged sympathetic effects.

These sympathetic effects include increased energy and socialization.

This gives a step by step understanding of what is happening without getting to the big picture ‘observables’—like rapid speech.

In the same way, an economist (asked by a business) might say, regarding Lasch’s commentary:

[fear of commitment] Consumers put a premium on having high optionality, even if they’re very unlikely to change. As a business, we can offer shorter term contracts at a premium price point to capture this preference.

We can also aim our marketing to show the great opportunities that would be missed by being ‘stuck’ in a long term arrangement.

[fear of aging] We’ve reached saturation for sick customers’ use of healthcare. As a business, we can penetrate the healthy market segment with grandiose theories of immortality, and sell them expensive tests.

If the consumer market is no longer terrified of death, our margins are going to collapse.

[boundless admiration for fame] Tik tok and Onlyfans are two companies that provide just enough value to change behavior in their creator-base, but are able to scoop vast oceans of wealth without actually creating anything of their own.

Any time we can, we should push for news articles showcasing absolutely crazy payouts for top creators—this form of marketing will seem more authentic, but acts as promotional material to convince other creators to do minimally paid labor.

Each of the complaints that Lasch raised are either caused by or greatly exacerbated by un-impeded capital flows. If there were moral or social guiderails against lies of immortality or virtual prostitution, then the capital could be kept in check.

Without that, economists have described the mechanism of action for a sick, current-day economy.

This is an example where Veblen and Baudrillard really step in with a more expansive philosophy than just supply/demand.

Veblen describes luxury Veblen goods.

Baudrillard describes the ‘sign’ or status value of items more formally.

These value metrics provide a more nuanced understanding of human behavior when it comes to incentives. Pretending that someone thinking a job is ‘sexy’ at a cocktail hour is worth $0 is a crazy misrepresentation of the real world.

There’s a reason that ‘boring’ industries tend to be some of the most profitable—more of the value of the enterprise is being returned to investors in the form of capital.

A part-owner of the coolest club in town is compensated for a lower capital return by being able to hang out with attractive women. An owner of a waste management company is not.

A fully globalized audience will change the output of a studio looking to maximally capitalize their AI lineup

Personally, I find it hard to know that is true ‘controversy’ vs manufactured equivalent. Are people actually mad about the recent Sydney Sweeny ads? Or are they reacting to what they believe is others’ anger—trying to show that they’re one of the good guys for showing outrage?