Note: This is a series of posts pulled from an interview session with Logan, the founder of Greco Gum (a sap-based mastic gum priced in the premium/superpremium range).

Check out their website to get an idea of their product and branding before reading on.

The Q&A section is edited for clarity and reordered for flow. Words and phrasings were retained wherever possible.

The posts in this series will cover the following topics:

Brand Identity

Company Future & What is Success?

Introduction

Many companies become successful at some point.

Not many companies stay successful for long.

When a company becomes temporarily successful, there’s a Great Filter that prevents them from becoming a durably successful company—the temptation to cut corners as they grow beyond personal relationships.1

It’s actually so common that not cutting corners during growth is an edge case (ha!).

In this post, we’ll be discussing how Greco Gum, through an ethos of high-quality work throughout the customer experience forged a brand identity, but not without significant costs.

Many brands position themselves as authentic, high-quality, and reliable and find success.

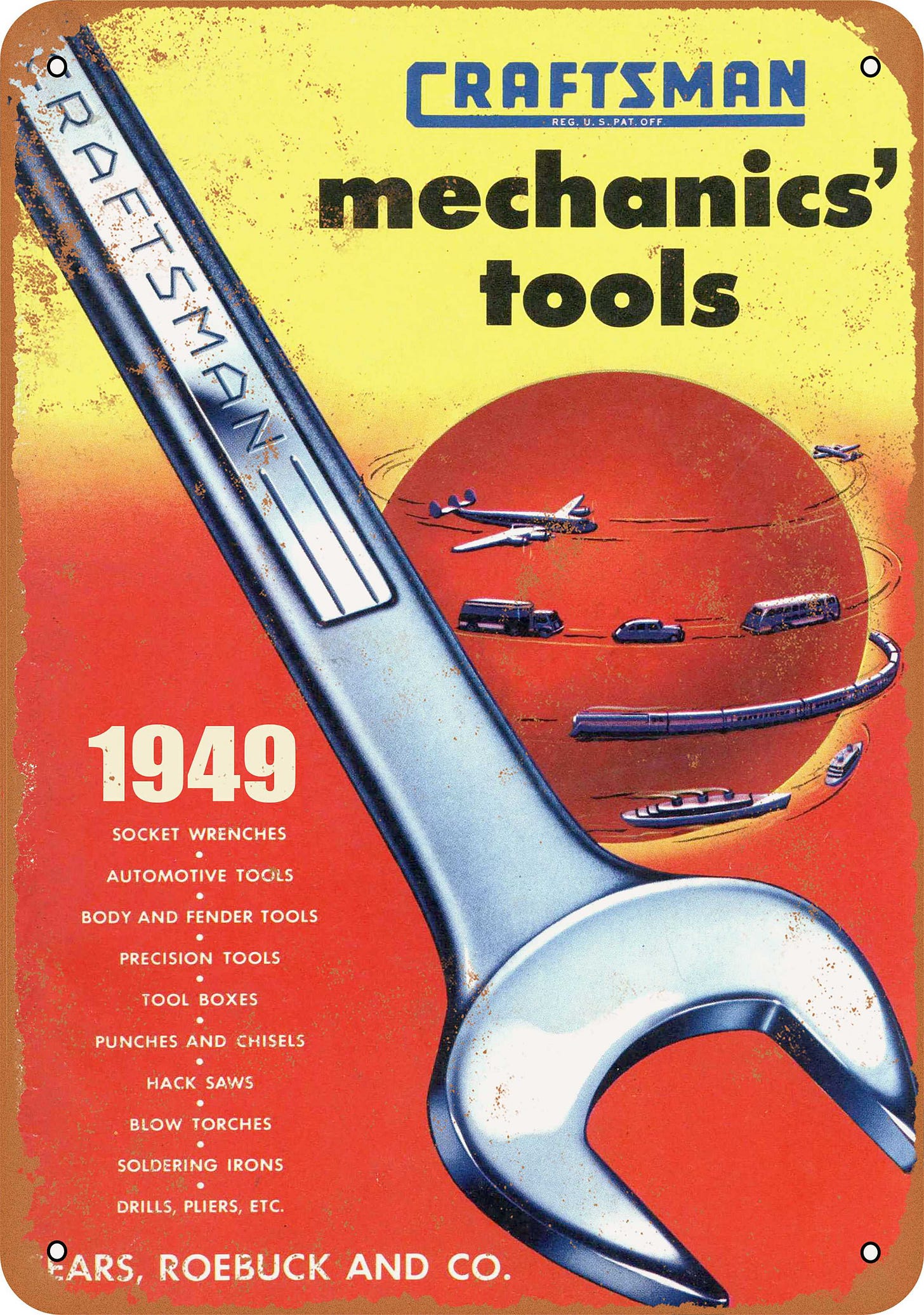

Think of Craftsman throughout most of the 20th century.

My grandfather loved the Craftsman tools of the past—made in America, tightly tolerances, and strong enough to pass along to the next generation. Like many others, he was pretty loyal to the company.

In 2010, back when Sears owned the brand, production of the tools was moved to China in an effort to cut costs and continue to capture the entry-level market.

Not content with the profit jump from lower labor costs, the cost cutting genie was let out of the bottle. The company began coasting on it’s reputation to continue to justify the costs for their tools.

Unfortunately, Chinese-made Craftsman tools performed significantly worse than Craftsman USA tools.

Despite technically still doing the job they were meant to do, the new tools disappointed customers.

Cutting costs and corners cut loyalty as well.2

The opposite can be true as well—sometimes not giving customers what they say they want can be better for a brand—As long as you don’t cut corners.

In the case of Greco Gum, their reliance on nature to produce their product means that they’re often out of stock.

Customers want to buy what they want & when they want it.

Except they don't

Product Supply

Q: I did see that you don't sell things continually throughout the year. [Instead you sell] in bits and spurts drops, which seems more like the structure of luxury product goods rather than any commodity.

You could buy a banana year round, but you couldn't buy any specific Louis Vuitton bag whenever you want.

Logan: Not intentional at all.

If I could make money year round, I certainly would.

We’re not like brands like Rolex who have a million watches to sell, but they're only going to give their authorized dealers for a couple of months to make artificial scarcity to increase the demand.

In a way, I think that [inconsistent stock] did help give us that same kind of charm as those luxury brands.

In the long term it has benefited us, but at the beginning I was pulling my hair out

I was getting messages from people every day saying, “Hey, when is it getting back in stock?”

[I hated saying] “Check back in 2 months”

Even then, I'm at the mercy of the growers and making sure they're going to have enough to give me. There's so many hurdles to make sure to finally get the end good into the consumer's hands.

Customer Satisfaction

Q: Have you had any issues with customers being unhappy with whatever ends up arriving and how did you deal with that?

Logan: Very rarely.

And that's because we do everything ourselves.

We're hand packing every tin.

We're filtering through it.

We're sifting all of the garbage pieces out just to avoid situations like that.

The worst case scenario for us is if somebody gets something, they're disappointed, and they're not going to give us another chance again.

So we go to great lengths to avoid that, but it does happen where somebody isn't happy with the product, and that's unavoidable.

Usually that issue is more of their expectations of what [our product] is.

If [a customer orders our gum] thinking it's like Hubba Bubba, you're setting yourself up for disappointment.

But we're also not trying to be those things.

In fact, we're the antithesis of those products. And those people who resonate with that are our customers.

Logan’s customers are happy.

Logan shows that his customer base is only "very rarely” unhappy with the product, despite breaking ‘common sense’ business rules. This willingness to depart from the MBA-itized obsession with consistency marks Greco Gum as unusual in the marketplace and became part of their brand.

Logan couldn’t keep the product on shelves

He could have accepted larger shipments of lower grade mastic

Logan couldn’t grow as quickly as his customers wanted

He could have franchised out to grow faster

Logan provided one product and one product only.3

He could have expanded outside an area of personal experience

But what he provided was consistently high-quality, and mission-aligned.

No corners cut—customers stay happy

Diving deeper into what built loyalty among the customer base, Logan mentioned the unique feel of the brand.

He mentions the feeling of a small company, matching the ad tones to the channel used, and providing customers a visual goal for a life that they can aspire to.

Consistent Ad Direction

Logan: One of your questions was about how we maintain this brand image of masculinity and strength.

How do we maintain this brand image while still appealing to a large audience?

Two points:

[It feels like] every advertisement you see now features ugly and unhappy people…they're not smiling [when interacting with the product].

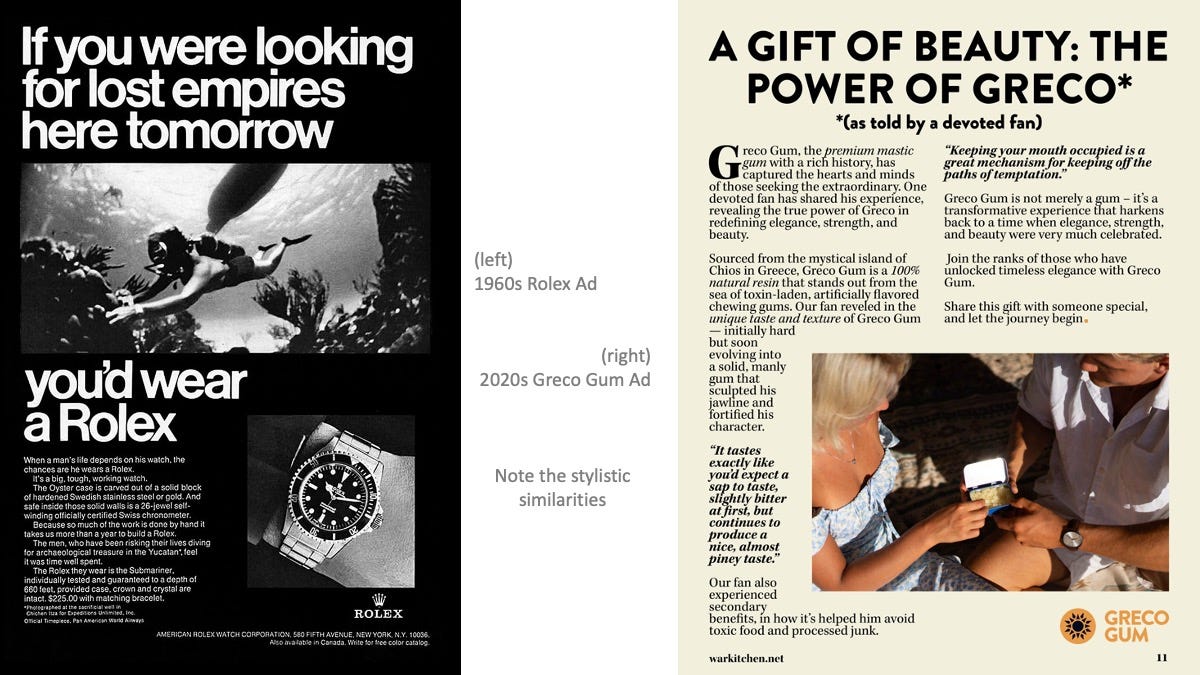

When you look back at some of the most memorable or the best advertisements, they're all decades old. Whether that's the Rolex ads from the 60s or Polo Ralph Lauren or Calvin Klein ads of the 80s, [they] showcase beautiful imagery.

It always was beautiful people [and people] doing cool things, things that you would look at that and say something like:

Oh, wow. I wish that I wish that were me.

I want to do that!

That looks appealing

I want to return to that aspirational style of marketing.

[Within ads and products, you see the idea that] unacceptable standards should just be tolerated and normalized, and that's that's not what we are about.

And the second part of that question: How do we how do we maintain this image while still keeping to our audience?

Well, to that, we're not for everyone.

We're not trying to, and we can’t appeal to everyone.

There's very certain type of person that we're marketing to, but that audience is large.

So many people who feel the that they have been deprived of this type of messaging or marketing and they’re begging for [something to aspire to], so we'll give it to them.

Much like in the last article, Logan’s answers show a fixation on obsessively satisfying the needs of a specific market rather than making an attempt to vaguely satisfy everyone and risking neutering the marketing materials.

The product and the marketing are designed to make loyal fans from a small market instead of passive purchasers in larger numbers.

Judging Successful Content

Q: How did you judge an ad or campaign as successful?

Logan: It's interesting because the the posts or the tweets or whatever that tend to do the best are the ones I’m lukewarm on.

The ones like I really like or the ones I put a lot of thought into tend to flop.

And that's just goes to show it's really tough to predict what will resonate and what won't.

Benchmarks for success

Q: Is there anything that you all benchmark up against?

Logan: At the end of the day, [the benchmark is] sales generated.

But in some of our emails, the call to action isn't to make a sale.

It's telling a story and crafting that personality behind the brand. Our goal [for those] is…to get people to reply to the e-mail.

We’re not comparing to others. We’re benchmarking against our previous selves.

Conclusion

Because Greco Gum pursued a business strategy not taken by the majority of companies, benchmarking success, growing quickly, and keeping consistent product supply were much more difficult than a more common ‘growth-at-any-costs' business plan.

But, it worked for them.

The alternative did not work for the long-term success of Craftsman

Obsess about satisfying your customers

Interestingly, sometimes cutting corners accidentally works better than perfectly arranging things. For example, the Germans ‘invented’ radar, but built the first prototypes so perfectly that they weren’t able to generate the natural rotation and resonance needed for correct operations. The Brits had no issues building an asymmetrical system. (German invention first. Did not get the ranging effects needed for aircraft radar)

Snap-On, although expensive, is my grandfather’s new favorite

There are 2 variations currently available, but they’re the same material from the same source. They’re just sorted by size